Patient Engagement in Drug Development: The Rise of Patient-centric Approaches

By Team Medical Advising & Clinical Safety

The concept of patient centricity has emerged over the last three decades [1]. Although no clear definition of patient centricity exists and the scope for interpretation is wide, putting the patients‘ needs in the centre and systematically engaging patients in drug development activities and decision making could be seen as an essence of existing definitions.

The following definitions are some examples how patient centricity is described by health authorities and in the literature:

- „The recognition of the needs of an individual patient or distinct patient populations and their specific needs as the focal point in the overall design of a medicine including the targeted patients’ physiological, physical, psychological, and social characteristics.“ [2]

- “Putting the patient first in an open and sustained engagement of the patient to respectfully and compassionately achieve the best experience and outcome for that person and their family.” [3]

- „We define patient centricity as fulfilment of patient needs.“ [4]

- “Ensuring that patients’ experiences, perspectives, needs, and priorities are meaningfully incorporated into decisions and activities related to their health and well-being.” [5]

Efforts were made to define patient centricity from the perspective of a patient [3,6]. For patients and patient organisations medical education and communication using plain language, co-creation (e.g. the dialogue of researchers with patients, patient input in trial design such as end point selection, etc.), easy access to medicines and related information as well as transparency regarding clinical trial data were defined as important principles of patient centricity [3,6].

The engagement of patients in the development of new therapies has been recognised as a valuable strategy, and an increasing number of pharmaceutical companies are implementing patient-centred activities [7]. Involving patients throughout the entire development process, i.e. throughout the lifecycle of a product, holds the potential to provide key information and valuable insights from patients. Understanding of the disease and its impact on patients’ daily lives, identifying unmet medical needs, considerations related to clinical trial design, selection of clinically meaningful endpoints, and requirements regarding e.g. drug formulation are key points of patient-centric approaches [8]. The importance of patient input into drug development has also been recognised by regulatory authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The ICH E8 (R1) Guideline “General Considerations for Clinical Trials” that came into effect on 14 April 2022 has set patient-focused drug development as a key priority. It strongly encourages the involvement of patients and patient organisations at all stages of drug development, as it “is likely to increase trust in the trial, facilitate recruitment, and promote adherence” [9]. This is supported by the ICH Good Clinical Practice E6 (R3) Draft Guideline that recognises the input of patient in trial design as important factor to ensure quality and meaningful trial outcomes [10].

Anticipated benefits for the pharmaceutical industry are facilitating successful and efficient patient recruitment and enrolment while minimising drop-out rates and thereby accelerating clinical trials [4,8]. Furthermore, an early identification of patient relevant outcomes and the input by patients in trial design may lead to an overall improvement of study quality. In turn, patient-centric activities have the potential to save costs, as poor recruitment and retention, as well as failure to adequately address patients’ needs during early development, can have costly long-term consequences for a product’s success throughout the clinical and post-authorisation stages [8].

Patient-centric drug development

As a first step of patient-centric drug development, the real needs of patients and caregivers should be identified in a broad and representative population, as needs vary across individuals, diseases and cultures [4,11]. Insights into the impact and burden of the disease on daily life and priorities from the perspective of patients and caregivers can be gathered using qualitative and quantitative research methods such as questionnaires, personal interviews, or discussions with patients and patient representative groups [4,8].

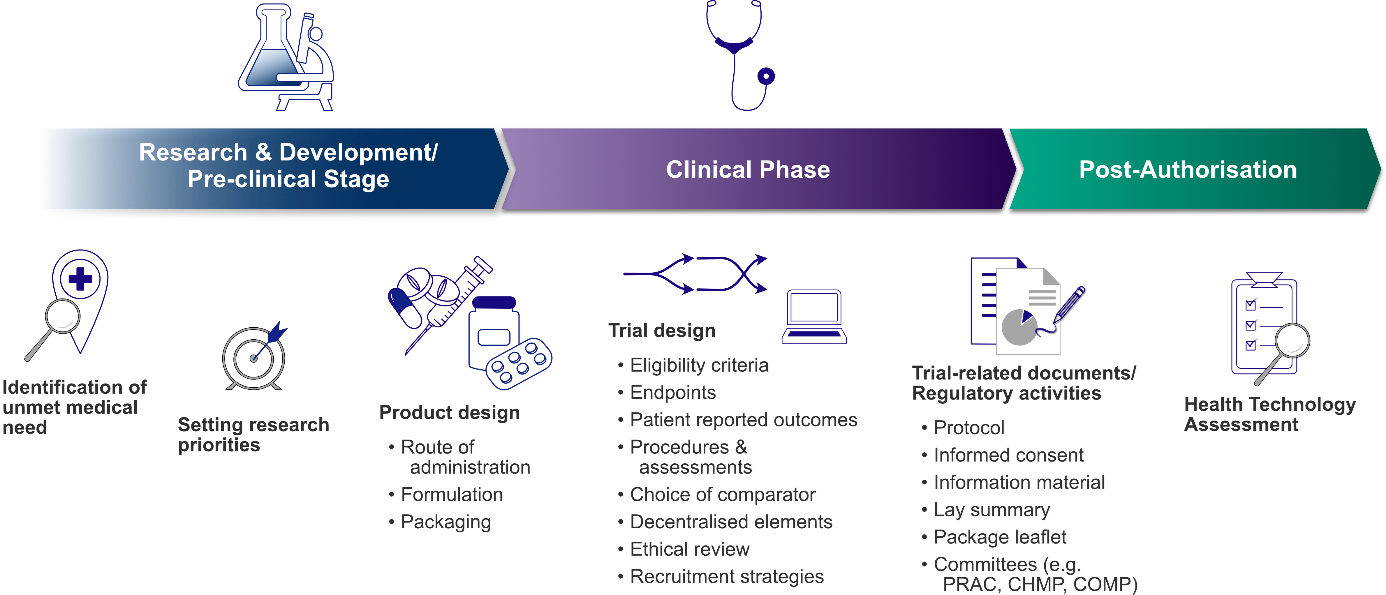

Figure 1: Patient involvement in drug development throughout the product lifecycle

1. Research & development phase and pre-clinical stage

At the stage of early research & development, patient input can be sought to identify specific therapeutic areas with a high medical need and set research priorities accordingly [8]. Characterisation of the intended patient population is important to ensure that products of interest for clinical development meet patients’ needs. Incorrect prioritisation might lead to wrong decision during the product‘s development programme potentially bearing high costs at a later stage [8,12]. Incorporating patient input at early stages of drug development holds the potential of the most impact of patient voices.

At the pre-clinical stage, the assessment of patient preferences in pharmaceutical design aspects, such as formulation, route of administration, administration setting (inpatient versus outpatient), dosing schedule, flexibility in dosing and packaging, is of great value in facilitating product acceptance and treatment adherence [2,8,13]. Therefore, product developers must consider certain needs and abilities for specific patient populations. For instance, for geriatric patients easy handling of packaging (e.g. easy-to-open containers) and swallowability of solid oral dosage forms are essential. In paediatric patients age-appropriate formulations, high dosing flexibility and the palatability of oral medicines are further crucial factors for acceptance [9,13]. Furthermore, cultural preferences might also affect product design. As an example, in countries with a significant stigma of HIV the characteristic sound of pill bottles when carried, revealed HIV patients [11], indicating that the primary packaging was not suitably designed under these social circumstances. In certain countries the right choice of route of application is critical, as due to cultural issues a rectal route of administration might not be accepted and therefore not feasible [14].

2. Clinical stages of product development

Incorporating patient input into clinical trial design is of great value and highly encouraged by the ICH E8 guideline [9]. Patients, as potential study participants and key stakeholders, can provide input for clinical trial design with their perspectives in all aspects.

- Eligibility Criteria: Is the intended trial population representative? Is enrolment feasible under proposed eligibility criteria?

- Endpoints: Which outcomes are relevant to patients? Are selected endpoints clinically meaningful for the targeted population?

- Choice of Comparator: Which comparator is acceptable and reflects real-world clinical practice?

- Study duration and procedures: Are the scheduled study visits and procedures appropriate and not too burdensome?

Patients can be actively engaged in the development of trial protocol and other trial-related documents such as informed consent and trial information material as well as planning of recruitment strategies. As members of ethics committee, patients and patient representatives perform ethical review. For alleviating the burden for trial participants decentralised clinical trials may be a right approach. Using decentralised elements such as telemedicine, remote monitoring via wearable devices and collection of efficacy parameters such as patient reported outcomes in electronic forms (ePRO), just to mention a few, can reduce the amount of travel to potentially distant trial sites. Hence, decentralised elements can facilitate recruitment and retention and can increase inclusion and diversity in clinical trials. Moreover, trial activities taking place at home in familiar environment can increase the patient‘s comfort, flexibility and are easier to integrate in everyday life [4].

3. Late-phase and post-marketing:

As part of the patient-centric concept, early access programmes, also known as “compassionate use”, can address highly unmet medical need in the advanced stages of product development [8]. Investigational products in late stages can be made available before authorisation to patients with life-threatening and/or seriously debilitating disease that cannot be treated satisfactorily with any currently authorised therapy and who cannot participate in clinical trials.

Patient engagement is highly recommended in the development of the lay summary of clinical trial results [9]. For this and other documents that are intended for patients, such as the package leaflet, a user-testing with lay persons should be conducted to ensure readability and comprehensibility e.g. the ability to follow the instructions for use [2,15]. After authorisation of the product, patient feedback can be sought proactively for early identification of potential issues and patient surveys can be conducted to obtain real-world data on use and satisfaction [8]. Patient input is also essential for the evaluation of the value of therapies within the scope of health technology assessment (HTA).

Approaches of patient-centric initiatives

In 2012 FDA initiated the Patient-Focused Drug Development Program [16]. The agency provides guidance documents for best practices in identifying target populations, collecting input, developing clinical outcome assessments and their incorporation into endpoints. It also provides recommendations for specific patient populations (e.g. paediatric, geriatric) [17]. Also EMA actively supports patient engagement throughout the medicine lifecycle [18]. Patient representatives are included as members in scientific committees such as the EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC), Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) and Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) [18]. Furthermore, patients are consulted on disease-specific issues by the scientific committees and are involved in reviewing of documents intended for public as well as in the development of guidelines [19]. In HTA activities patients are involved by HTA bodies through public consultations and appraisal committees [20]. Furthermore, an involvement of patients and healthcare professionals as external experts via joint scientific consultations and clinical assessments is planned within the scope of the European network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA) [21].

Also pharmaceutical industry and academia have made efforts to implement patient-centric initiatives in drug development and research. Some approaches are:

- Collaborations/ partnerships e.g. patient and physician advisory boards [7,22],

- Incorporation of decentralised elements in clinical trials e.g. technology solutions such as telemedicine, home nursing, direct-to-patient shipment of medicine [7,22],

- Educational/ transparency activities e.g. lay summary, co-creation of trial information in lay friendly language including visualisation [1,7,23],

- Crowdsourcing of clinical trial protocols – an internet-based platform to inform clinical trial design by collecting input of patients/ advocates as well as physicians and researchers [24],

- Social media listening studies/ patient preference studies [25],

- Development of novel PRO based on input from patient advocacy groups and caregivers [26].

Examples of organisations that are regularly involved in the product development process are the European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI), a public-private framework, and the Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), a non-profit organisation [27,28]. The online portal EUPATIConnect offers the opportunity to get in touch with patient experts for specific activities such as protocol review, patient advisory boards and development of lay summaries for instance. Furthermore, EUPATI offers guidances for structured patient involvement in industry-led drug development, HTA, regulatory processes and ethics committees.

Summary

Patient-centric approaches in drug development are anticipated to bear benefits for both, patients and sponsors. Patient engagement activities such as the involvement of advocacy groups, conduction of patient advisory panels and focus groups were found to have a high impact and to be cost-effective [1]. As already demonstrated by real examples, patient-centric activities in clinical trials have improved recruitment and participant retention, reduced the number of protocol amendments and accelerated approval resulting in saving of costs [1,4]. Decentralised clinical trials or trials with decentralised elements (hybrid trials) that provide various benefits, such as less burden and more convenience for patients, better data quality, faster accessibility of results and many more, are increasingly on the rise. The concept of patient centricity is a win-win situation for all parties involved. Let’s turn patient-centric theory into reality and put the patients in the centre of the decision making.

References

- S. Stergiopoulos, D.L. Michaels, B.L. Kunz, K.A. Getz, Measuring the Impact of Patient Engagement and Patient Centricity in Clinical Research and Development, Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 54 (2020) 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-019-00034-0.

- S. Stegemann, R.L. Ternik, G. Onder, M.A. Khan, D.A. van Riet-Nales, Defining Patient Centric Pharmaceutical Drug Product Design, AAPS J. 18 (2016) 1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-016-9938-6.

- G. Yeoman, P. Furlong, M. Seres, H. Binder, H. Chung, V. Garzya, R.R. Jones, Defining patient centricity with patients for patients and caregivers: a collaborative endeavour, BMJ Innov. 3 (2017) 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2016-000157.

- T. van Iersel, J. Courville, C. van Doorne, R.A. Koster, C. Fawcett, The Patient Motivation Pyramid and Patient-Centricity in Early Clinical Development, Curr. Rev. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. 17 (2022) 8–17. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574884716666210427115820.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Patient-Focused Drug Development Glossary, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/patient-focused-drug-development-glossary.

- D. Amin, P. Vandenbroucke, Advancing patient-centricity in Medical Affairs: A survey of patients and patient organizations, Drug Discov. Today 28 (2023) 103604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103604.

- D.L. Michaels, M.J. Lamberti, Y. Peña, B.L. Kunz, K. Getz, Assessing Biopharmaceutical Company Experience with Patient-centric Initiatives, Clin. Ther. 41 (2019) 1427–1438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.07.018.

- M. Algorri, N.S. Cauchon, T. Christian, C. O’Connell, P. Vaidya, Patient-Centric Product Development: A Summary of Select Regulatory CMC and Device Considerations, J. Pharm. Sci. 112 (2023) 922–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2023.01.029.

- EMA, ICH guideline E8 (R1) on general considerations for clinical studies, 2021.

- EMA, GOOD CLINICAL PRACTICE (GCP) E6(R3): Draft version, 2023.

- M.D. Burke, M. Keeney, R. Kleinberg, R. Burlage, Challenges and Opportunities for Patient Centric Drug Product Design: Industry Perspectives, Pharm. Res. 36 (2019) 85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-019-2616-5.

- A. Hoos, J. Anderson, M. Boutin, L. Dewulf, J. Geissler, G. Johnston, A. Joos, M. Metcalf, J. Regnante, I. Sargeant, R.F. Schneider, V. Todaro, G. Tougas, Partnering With Patients in the Development and Lifecycle of Medicines: A Call for Action, Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 49 (2015) 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/2168479015580384.

- S. Page, T. Khan, P. Kühl, G. Schwach, K. Storch, H. Chokshi, Patient Centricity Driving Formulation Innovation: Improvements in Patient Care Facilitated by Novel Therapeutics and Drug Delivery Technologies, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 62 (2022) 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-052120-093517.

- S. Hua, Physiological and Pharmaceutical Considerations for Rectal Drug Formulations, Front. Pharmacol. 10 (2019) 1196. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01196.

- European Commission, Good Lay Summary Practice: Version 1, 2021. https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-10/glsp_en_0.pdf (accessed 3 November 2022).

- FDA, Evolution of Patient Engagement at the FDA. https://www.fda.gov/patients/evolution-patient-engagement-fda.

- FDA, FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Series for Enhancing the Incorporation of the Patient’s Voice in Medical Product Development and Regulatory Decision Making, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/fda-patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-series-enhancing-incorporation-patients-voice-medical (accessed 1 September 2023).

- EMA, Patient engagement: from a patient centric drug development to authorisation: 10th Industry Stakeholder Platform on the Centralised Procedure, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/presentation/presentation-patient-engagement-patient-centric-drug-development-authorisation-m-mavris-ema_en.pdf.

- EMA, Patients and consumers. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/patients-consumers#activities-of-patients-and-consumers-section.

- European Patients’ Forum, Patient Involvement in Health Technology Assessment in Europe: Results of the EPF Survey, 2013.

- EUnetHTA 21, D7.2 – GUIDANCE ON PATIENT & HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL INVOLVEMENT: Version 1.0, 04.04.2023, 2023.

- M.J. Lamberti, J. Awatin, Mapping the Landscape of Patient-centric Activities Within Clinical Research, Clin. Ther. 39 (2017) 2196–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.09.010.

- Boehringer Ingelheim, Mutual benefit: Patient centricity in clinical trials. https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/human-health/our-responsibility/patient-centricity/mutual-benefit-patient-centricity-clinical (accessed 1 September 2023).

- A. Leiter, T. Sablinski, M. Diefenbach, M. Foster, A. Greenberg, J. Holland, W.K. Oh, M.D. Galsky, Use of crowdsourcing for cancer clinical trial development, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju258.

- O. Zvonareva, C. Craveț, D.P. Richards, Practices of patient engagement in drug development: a systematic scoping review, Res Involv Engagem 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-022-00364-8.

- T. Klopstock, M.L. Escolar, R.D. Marshall, B. Perez-Dueñas, S. Tuller, A. Videnovic, F. Greblikas, The FOsmetpantotenate Replacement Therapy (FORT) randomized, double-blind, Placebo-controlled pivotal trial: Study design and development methodology of a novel primary efficacy outcome in patients with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration, Clin. Trials 16 (2019) 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774519845673.

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation, Homepage. https://eupati.eu/.

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Homepage. https://www.pcori.org/.

Picture: @ Kiattisak/AdobeStock.com